Overview

After you decide to invest in bonds, you then need to decide what kinds of bond investments are right for you. Most people don’t realize it, but the bond market offers investors a lot more choices than the stock market.

Depending on your goals, your tax situation and your risk tolerance, you can choose from municipal, government, corporate, mortgage-backed or asset-backed securities and international bonds. Within each broad bond market sector you will find securities with different issuers, credit ratings, coupon rates, maturities, yields and other features. Each one offers its own balance of risk and reward.

Use this section to clarify the differences among your bond investment alternatives:

- Learn the ins and outs of different types of bonds in the comprehensive “Investor’s Guides” to various types of bonds

- Supplement your knowledge with product-focused industry research and articles

- Find out more about bond funds

To purchase Investor Guides in digital format as a site license, please visit: www.sifma.org/store.

What are Municipal Bonds?

Municipal bonds—sometimes known as “munis”— are debt obligations issued by state and local governments, as well as agencies and authorities like school districts and public utilities, to fund public projects. Such projects include construction and repair of roads, schools, hospitals, water and sewer systems, and other public works.

When you purchase a municipal bond, you are lending money to the state or local government entity that issued the bond. In turn, the issuer promises to pay you a specified amount of interest (usually paid twice per year) and return the principal on a specified maturity date.

While many municipal bonds offer income exemption from both federal and state taxes, not all munis have these tax features. There is an entirely separate market of municipal issues that are taxable at the federal level – as part of the Alternative Minimum Tax – but still offer a state or local tax exemption on interest paid to residents of the state of issuance. In addition, there are other types of municipal securities that are taxable at the federal, state and local levels.

Most of the information in this guide refers to municipal bonds that are exempt from federal taxes. Refer to information on taxable municipal bonds.

Note: SIFMA does not provide tax advice, and the tax information and chart provided in this guide are not intended to be a substitute for a consultation with a tax professional who knows the characteristics of the bond and your tax circumstances. A tax professional can help explain the tax implications of investing in municipal bonds and other securities.

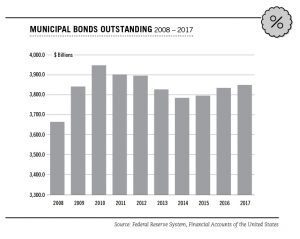

How Large is the Tax-Exempt Municipal Bond Market?

Outstanding state and local debt obligations totaled $3.85 trillion as of December 31, 2017.

The majority of tax-exempt municipal securities are owned by individuals, mutual and money market funds, commercial banks, and property and casualty insurance companies.

Why Invest in Municipal Bonds?

Tax-exempt municipal bonds are among the most popular types of investments available today to individual investors.

They offer a wide range of features, including:

- Attractive current income, free from federal and, in some cases, state and local taxes;

- Credit quality with regard to payment of interest and repayment of principal;

- Predictable stream of income;

- Wide range of choices to meet investment objectives regarding investment quality, maturity, choice of issuer, type of bond and geographical location; and

- Marketability in the event an investor decides to sell before maturity

Credit Quality

Tax-exempt municipal bonds offer investors the chance to maximize the after-tax return consistent with their level of risk tolerance. In general, as with any fixed-income investment, the higher the yield, the higher the risk.

When you invest in a municipal bond, the primary concern should be the issuer’s ability to meet its financial obligations. Issuers of municipal bonds should have a record of making interest and principal payments in a timely manner.

To learn about an issuer’s financial condition, visit the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board’s (MSRB) Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) portal at emma msrb org to obtain the issuer’s official statements or offering document. These documents may also be obtained from a bank, financial professional, or online sources. Issuers provide continuing disclosure about their financial condition, which is also available on EMMA, and you can contact the issuer or visit their website for the most current information.

CREDIT RATINGS

An issuer can be evaluated by examining its credit rating. Bond ratings are important benchmarks because they reflect a professional assessment of the issuer’s ability to repay the bond’s face value at maturity.

Many bonds are graded by ratings agencies such as Moody’s Investors Service, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings.

Generally, bonds rated BBB (Standard & Poor’s and Fitch) or Baa (Moody’s) or higher are considered “Investment Grade.” Bonds with lower ratings are considered high yield, or speculative.

The Features of Tax Exemption

Under current federal income tax law, interest income earned from investing in many types of municipal bonds is not subject to federal income taxes. In most states, interest income received from securities issued by the state, or government entity within that state, is also exempt from income tax imposed by that state and/or its political subdivisions. In addition, interest income from bonds issued by U S territories and possessions is exempt from federal, state and local income taxes in all 50 states.

One of the best ways to measure the tax-exempt benefit of a municipal bond is to compare it to a taxable investment. For example, assume that an investor is in the 32% federal tax bracket, files a joint return with their spouse, and claims $335,000 in taxable income.

Now assume that investor has $30,000 to invest and they are considering two alternative investments: a tax-exempt municipal bond yielding 3% versus a taxable corporate bond yielding 4%.

If that investor buys the municipal bond, they would earn $900 per year in interest (a 3% yield) and pay no federal income tax on the interest income. As noted in the table below, the taxable bond investment with a yield of 4% would, however, provide the investor with only $816 in income after federal taxes (a 2.7% after-tax yield).

The municipal bond in this example would provide a higher net yield after taxes. The tax-exempt bond’s yield differential would be higher if the investor also accounted for state and local income taxes when calculating returns on the taxable bond investment.

Understanding Yields

Yield is the rate of return on a bond investment. There are two basic types of bond yields: current yield and yield to maturity.

Current yield is the interest “coupon” divided by the dollar amount paid for a bond.

Yield to maturity is the rate of return you receive by holding a bond until it matures. It equals the interest you receive from the time you purchase the bond until maturity, plus or minus any difference between the price you pay for the bond and the amount you receive at maturity. It also accounts for the reinvestment of interest income at the same assumed rate.

Tax-exempt yields are usually stated in terms of yield to maturity or yield to call, whichever is lower, with yield expressed as an annual rate. If you purchase a bond with a 3% coupon at par, for example, its yield to maturity is 3%. If you pay more than par, the yield to maturity will be lower than the coupon rate. If purchased below par, the bond will have a yield to maturity higher than the coupon rate. When the price of a tax-exempt bond increases above its par value, it is said to be “selling at a premium.” When the security sells below par value, it is said to be “selling at a discount .”

Understanding Market Risk

Whether a bond pays the investor a fixed interest rate (also known as the coupon rate) or a variable interest rate, the market price of a municipal bond will vary as market conditions – primarily interest rates – change. If you sell your municipal bonds prior to maturity, you will receive the current market price, which may be more or less than the original price depending on prevailing interest rates at the time of sale.

For example, a municipal bond issued with a 2% coupon will sell at a premium if interest rates at the time of sale are below 2%. Consequently, it is important to understand that municipal bond prices fluctuate in response to changing interest rates: prices increase when interest rates decline, and prices decline when interest rates rise. It is also possible for the price of a bond to change if the credit quality of the borrower changes.

The inverse relationship between bond prices and yields may seem confusing at first. But it’s not that complicated if you recognize that:

- When interest rates fall, new issues come to market with lower yields than older securities, making the older bonds worth more, leading to an increase in price; and

- When interest rates rise, new issues come to market with higher yields than older securities, making the older bonds worth less— hence the decline in price.

Understanding Calls

Many bonds allow the issuer to call — or retire— all or a portion of the bonds at a premium, or at par, before maturity. One common reason an issuer may elect to call its bonds is if interest rates decline and they wish to refinance the debt at a lower rate. When buying bonds, ask a financial professional about call provisions, or the likelihood of the borrower possibly exercising its option to call the bond, and the difference between the yield to call and the yield to maturity.

GAINS AND LOSSES

If you sell a municipal bond or any other bond for a profit before it matures, you may generate capital gains or losses. Long-term capital gains – which require you to have held the investment for 12 months before selling – resulting from the sale of tax-exempt municipal bonds are currently taxed at a maximum rate of 20%. Of course, if you sell your security for less than your original purchase price, you may incur a capital loss.

Under current law, up to $3,000 of net capital losses can be used annually to reduce ordinary income. Capital losses can be used without limit to reduce capital gains. A municipal bond purchased at a “market discount” may be subject to special rules and may generate income that is taxable at ordinary income rates. Since tax laws frequently change, consult with a tax lawyer or accountant for up-to-date advice.

Types of Tax-Exempt Municipal Bonds

Municipal securities consist of both short-term issues (often called notes, which typically mature in one year or less) and long-term issues (commonly known as bonds, which mature after one year or more). Short-term notes are used by an issuer to raise money for a variety of reasons: in anticipation of future revenues such as taxes, state or federal aid payments, and future bond issuances; to cover irregular cash flows; to meet unanticipated deficits; or to raise immediate capital for projects until long-term financing can be arranged. Bonds are usually issued to finance or refinance capital projects over the longer term.

The two basic types of municipal bonds are:

GENERAL OBLIGATION BONDS

Principal and interest are secured by the full faith and credit of the issuer, and are usually supported by either the issuer’s unlimited or limited taxing power. General obligation bonds often require voter approval in a referendum.

REVENUE BONDS

Principal and interest are secured by revenues derived from tolls, charges or rents from the facility that was built with the proceeds of the bond issue. Public projects financed by revenue bonds include toll roads, bridges, airports, water and sewage treatment facilities, hospitals and subsidized housing. Many of these bonds are issued by special authorities created for that particular purpose. State and local government entities also issue municipal bonds in the form of revenue bonds in which the issuer loans the proceeds of the bonds to an underlying borrower who is a private entity, such as a non- profit college or hospital.

Bonds With Special Investment Features

Other key features a bond investor should be familiar with include:

VARIABLE RATE BONDS

The interest rate of these bonds is calculated periodically, and may be based on the prevailing rates for Treasury bills and other interest rates or on other factors.

PUT BONDS

Some bonds have a “put” feature, which allows you to sell the bond at par value on a specified date before its maturity date, and recoup the principal and accrued interest.

ZERO-COUPON, COMPOUND-INTEREST AND MULTIPLIER BONDS

These are issued at a deep discount to the maturity value and do not make periodic interest payments. At maturity, an investor will receive one lump sum payment equal to principal invested, plus interest compounded semiannually at the original interest rate. Because they do not pay interest until maturity, the prices of these bonds tend to be volatile. These bonds may be attractive to investors seeking to accumulate capital for a long-term financial goal, such as retirement planning or college costs.

INSURED MUNICIPAL BONDS

Some municipal bonds are backed by municipal bond insurance specifically designed to reduce investment risk. In the event of payment default by the issuer, an insurance company – which guarantees payment – will send you both interest and principal when they are due. Such a guarantee is based on the claims paying ability of the insurance company.

Taxable Municipal Bonds

On occasion, a municipal bond (or muni) issuer will issue taxable bonds. Muni bonds can be issued as taxable bonds because the federal government does not exempt from income tax interest paid on certain types of bonds that are eligible for tax credits or subsidy payments made directly to the issuer – for example, Build America Bonds (www treasury gov/initiatives/recovery/Pages/babs aspx).

Muni bonds will also be issued as taxable bonds where the bonds finance a project that has too much private business use and the debt service on the bonds is paid with funds derived from that private business use project. Examples of taxable muni bonds include those issued to finance items, such as investor-led housing, local sports facilities (where revenues other than generally applicable taxes will be used to pay debt service on the bonds), and borrowing to replenish an underfunded pension plan. An issuer may still elect to finance these large-scale projects through a bond issue, but investors will pay federal tax on the interest income.

Since they do not possess the same tax benefits as tax-exempt munis, taxable municipal bonds offer yields comparable to those of other taxable obligations, such as corporate bonds or bonds issued by US governmental agencies, rather than to those of tax-exempt munis. The growth of the taxable municipal market in recent years has been significant as these bonds have gained popularity as a source of local financing. Between 2013 and 2017 alone, over $149.5 billion in taxable municipals have been issued.

Other Basic Facts

INTEREST PAYMENTS

Interest on a long-term bond is paid semiannually, while interest on short-term notes is paid at maturity.

FORM OF ISSUANCE

Municipal bonds today are issued in registered form only, which means the investor’s name is registered on the issuer’s, or its agents’, books. Virtually all municipal bonds today are issued in book-entry form, in which an investor’s ownership is recorded through data entry at a central clearinghouse. In addition, the bank or financial professional will provide the investor with a confirmation that is a written record of the transaction.

With book-entry securities, physical transfer of certificates is not necessary. Registered and book-entry bonds offer protection and convenience to bondholders, including protection from loss or theft, automatic payment of interest, notification of calls and ease of transfer.

MINIMUM INVESTMENT

Most municipal notes and bonds are issued in minimum denominations of $5,000 or multiples of $5,000.

WHERE TO FIND LISTED PRICES

The Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) system (emma msrb org) provides real-time and historical trade data for municipal bonds, such as financial disclosures made by bond issuers and other market information. Additionally, you can find information online through various individual investor websites. Because quoted prices are typically based on $1 million lots and reflect a volume discount, prices on purchases and sales of smaller amounts may differ according to the size of the order. You can also receive price quotes from a municipal securities broker-dealer.

MARKETABILITY

Holders of municipal securities can sell their notes or bonds through any bank or securities dealer firm that is registered to buy and sell municipal securities.

REPORTING REQUIREMENTS

All tax-exempt interest must be reported on your annual tax return. This is simply a reporting requirement and does not affect the tax- exempt status of the security.

THE COSTS ASSOCIATED WITH INVESTING IN MUNICIPAL BONDS

Municipal securities are bought and sold between dealers and investors much like other debt instruments. The price an investor pays for a municipal security will include a dealer’s fees for the transaction.

Tax-Exempt and Taxable Yield Equivalents

The chart illustrates the amount of income you require from a taxable investment to equal the yield on a tax-exempt bond. To use the chart most effectively, follow the directions under the chart.

TAX-EXEMPT / TAXABLE YIELD EQUVALENTS FOR TAX YEAR 2018

| TAXABLE | INCOME* | ||||||

| Tax brackets – single return | Up to $9,525 | $9,526 to $38,700 | $38,701 to $82,500 | $82,501 to $157,500 | $157,501 to $200,000 | $200,001 to $500,000 | over $500,000 |

| Tax brackets – joint return | Up to $19,050 | $19,051 to $77,400 | $77,401 to $165,000 | $165,001 to $315,000 | $315,001 to $400,000 | $400,001 to $600,000 | over $600,000 |

| Federal income tax rates | 10% | 12% | 22% | 24% | 32% | 35% | 37% |

| TAXABLE YIELD | EQUIVALENTS (%) | ||||||

| Tax-exempt yields (%) | |||||||

| 1.00% | 1.11% | 1.14% | 1.28% | 1.32% | 1.47% | 1.54% | 1.59% |

| 1.50% | 1.67% | 1.70% | 1.92% | 1.97% | 2.21% | 2.31% | 2.38% |

| 2.00% | 2.22% | 2.27% | 2.56% | 2.63% | 2.94% | 3.08% | 3.17% |

| 2.50% | 2.78% | 2.84% | 3.21% | 3.29% | 3.68% | 3.85% | 3.97% |

| 3.00% | 3.33% | 3.41% | 3.85% | 3.95% | 4.41% | 4.62% | 4.76% |

| 3.50% | 3.89% | 3.98% | 4.49% | 4.61% | 5.15% | 5.38% | 5.56% |

| 4.00% | 4.44% | 4.55% | 5.13% | 5.26% | 5.88% | 6.15% | 6.35% |

| 4.50% | 5.00% | 5.11% | 5.77% | 5.92% | 6.62% | 6.92% | 7.14% |

| 5.00% | 5.56% | 5.68% | 6.41% | 6.58% | 7.35% | 7.69% | 7.94% |

| 5.50% | 6.11% | 6.25% | 7.05% | 7.24% | 8.09% | 8.46% | 8.73% |

| 6.00% | 6.67% | 6.82% | 7.69% | 7.89% | 8.82% | 9.23% | 9.52% |

| 6.50% | 7.22% | 7.39% | 8.33% | 8.55% | 9.56% | 10.00% | 10.32% |

| 7.00% | 7.78% | 7.95% | 8.97% | 9.21% | 10.29% | 10.77% | 11.11% |

| 7.50% | 8.33% | 8.52% | 9.62% | 9.87% | 11.03% | 11.54% | 11.90% |

HOW TO USE THIS CHART

1. Find the appropriate return (single or joint).

2. Determine your tax bracket by locating the taxable income category that you fall into. Taxable income is income after appropriate exemptions and deductions are taken. (The chart does not account for special provisions affecting federal tax rates, such as the Alternative Minimum Tax.)

3. The numbers in the column under your tax bracket give you the approximate taxable yield equivalent for each of the tax-exempt yields in the near left column.

For example: If you are single and have a taxable income of $92,000 ($175,000 if married filing jointly), you would fall into the 24% tax bracket. According to the chart, you would need to earn 5.26% on a taxable security to match a 4% yield from a tax-exempt security.

* The income brackets to which the tax rates apply are adjusted annually for inflation. Those listed above are for 2018.

The above chart also reflects the tax brackets and rates of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which was signed into law on December 22, 2017 and is effective from January 1, 2018.

Your individual tax circumstances can/may affect your effective marginal tax rate.

Glossary

Alternative Minimum Tax. The AMT is a secondary income tax system, which has its own set of rates and rules, separate from regular income tax. Taxpayers are required to determine their tax liability under both the regular income tax and the AMT and to pay whichever is greater. Under the AMT certain deductions and exemptions are disallowed, including the exemption for interest on private activity municipal bonds.

Book-entry. A method of recording and transferring ownership of securities electronically, eliminating the need for physical certificates.

Coupon. The feature of a bond that denotes the interest rate (coupon rate) it will pay and the date on which the interest payment will be made. In the case of registered coupons (see “Registered bond” in this Glossary), the interest payment is transferred directly to the registered holder. Bearer coupons are presented to the issuer’s designated paying agent or deposited in a commercial bank for collection. Coupons are generally payable semiannually.

Default. A failure by an issuer to: (i) pay principal or interest when due, (ii) meet non-payment obligations, such as reporting requirements or (iii) comply with certain covenants in the document authorizing the issuance of a bond (an indenture).

Discount. The amount by which the par (or face) value of a security exceeds its purchase price.

Face (or Par or Principal). The principal amount of a security that appears on the face of the bond.

High-yield bond (or junk bond). Bonds rated Ba (by Moody’s) or BB (by S&P and Fitch) or below, whose lower credit ratings indicate a higher risk of default. Due to the increased risk of default, these bonds typically offer a higher yield than more creditworthy bonds.

Interest. Compensation paid or to be paid for the use of assets.

Issuer. The entity, typically a government or a government agency or authority, which initially offers bonds for sale to investors. Often, the issuer is also the party responsible for making interest and principal payments on a bond, although sometimes that may be a different entity.

Liquidity (or Marketability). A measure of the relative ease and speed with which a security can be purchased or sold in a secondary market.

Marketability. See Liquidity

Maturity. The date when the principal amount of a security is due to be repaid.

Notes. Short-term bonds to pay specified amounts of money, secured by specified sources of future revenues, such as taxes, federal and state aid payments and bond proceeds.

Offering document (Official Statement or Prospectus). The disclosure document prepared by the issuer that gives detailed security and financial information about the issuer and the securities being issued.

Official statement. See Offering document

Par value. See Face

Premium. The amount by which the price of a bond exceeds its par value.

Principal. See Face

Private Activity Bonds. A PAB is a type of municipal bond that is issued by a government entity where more than 10 percent of the proceeds are used by a private business and more than 10 percent of the debt service is secured by a private business. In general, the interest on PABs cannot be tax-exempt unless the transaction meets certain criteria established in tax law. PABs are generally used in the context of public-private partnership transactions, for certain housing and economic development purposes, and other qualified uses.

Ratings. Designations used by credit rating agencies to give relative indications as to opinions of credit quality.

Security. Collateral pledged by a bond issuer (debtor) to an investor (lender) to secure repayment of the loan.

Registered bond. A bond whose owner is registered with the issuer or its agent either as to both principal and interest or as to principal only. Transfer of ownership can only be accomplished when the securities are properly endorsed by the registered owner.

Variable rate bond. A long-term bond with a periodically adjusted interest rate, typically based on specific market indicators.

Yield (or Current yield). The annual percentage rate of return earned on a bond calculated by dividing the coupon interest rate by its purchase (market) price.

Yield to call. The yield to call is a calculation of the total return of a bond if held to the call date. It takes into account the value of all the interest payments that will be paid until the call date, plus interest earned on those payments (using the current yield), the principal amount to be received on the call date and any gain or loss from the purchase price expressed as an annual rate.

Yield to maturity. The yield to maturity is a calculation of the total return of a bond if held to maturity. It takes into account the value of all the interest payments that will be paid until the maturity date, plus interest earned on those payments (using the current yield), the principal amount to be received and any gain or loss from the purchase price expressed as an annual rate.

Zero-coupon bond. A bond that does not make periodic interest payments; instead, the investor receives one payment, which includes principal and interest, at redemption (call or maturity).